Introduction

The Institute for Transnational Arbitration (ITA) hosted a virtual panel discussion on February 18, 2025, that brought together experts in arbitration, cryptocurrency, and crowdfunding. This insightful event explored the evolving landscape of dispute resolution in these rapidly growing sectors, highlighting both the challenges and opportunities they present. The panel featured a diverse array of distinguished professionals who gave not only the theoretical but also the practical aspects of dispute resolution in the crypto space, and they discussed how crowdfunding can be an invaluable tool to raise finances for both arbitration and litigation. The discussion also dove into the complexities of arbitrating crypto disputes, addressing regulatory uncertainties, enforcement issues, jurisdictional concerns, and the intersection of traditional arbitration mechanisms with decentralized financial models.

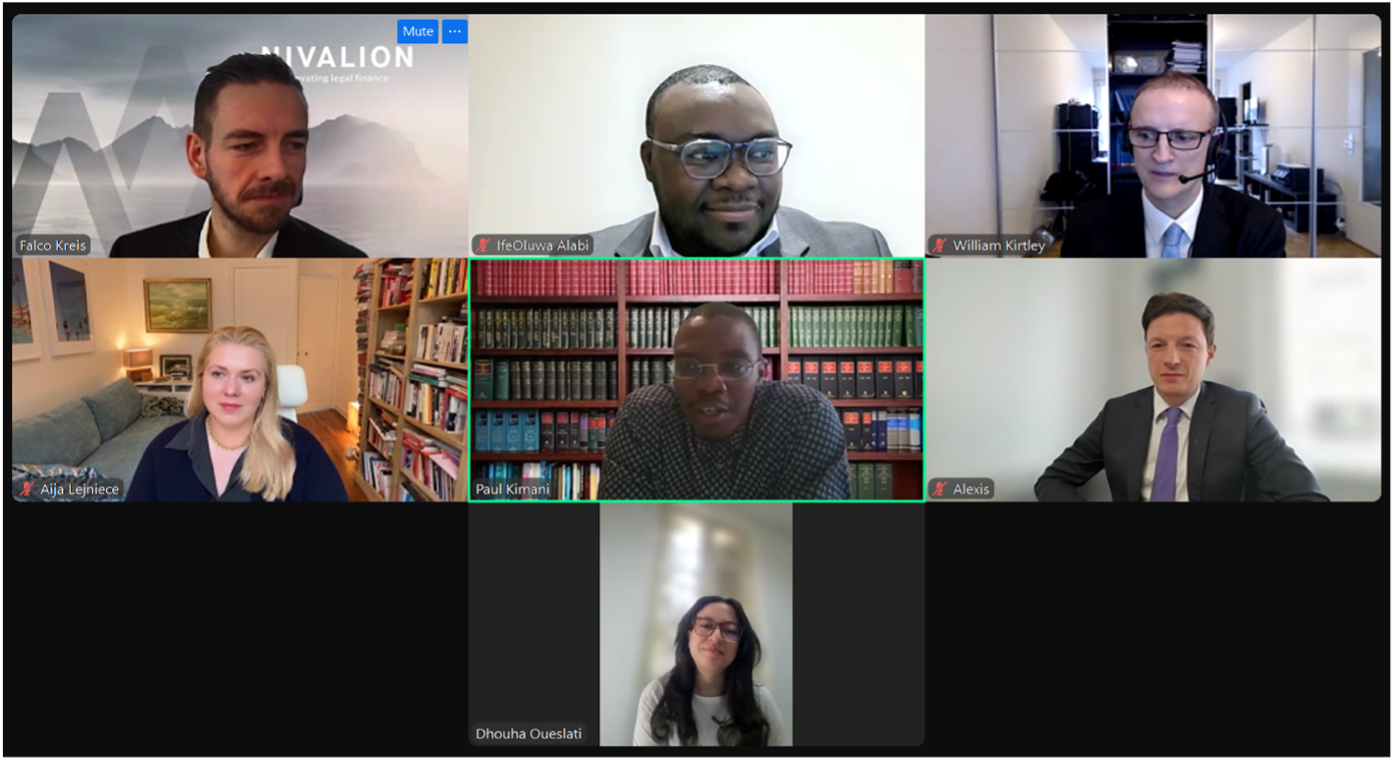

Moderated by Young ITA Africa Co-Chairs Dr. Paul Kimani and Dhouha Oueslati, the panel included Adam Mokrani (energy governance consultant, ICC YAAF representative for Africa), IfeOluwa Alabi (Hogan Lovells), Alexis Foucard (Clifford Chance), Aija Lejniece (independent counsel and arbitrator), William Kirtley (Aceris Law), and Falco Kreis (Nivalion).

Panel Discussions

Adam Mokrani started off the panel discussion by giving an overview of cryptocurrency and crowdfunding. He gave definitions and contrasted the two terminologies, highlighting that while cryptocurrency offers a decentralized digital currency, crowdfunding provides a platform that enables raising financial support for projects and ventures. He discussed the opportunities and future projections related to cryptocurrency and highlighted that governments are moving towards clearer regulations, which could provide more legitimacy to cryptocurrency and crowdfunding. Kenya, for example, introduced ‘The markets (Investment-based Crowdfunding) Regulations’ in 2022 to regulate crowdfunding, and it has introduced a ‘Virtual Assets Service Providers Bill, 2025’ intended to regulate virtual assets. Mokrani also noted that the future holds a perhaps fraud-free crypto world with improved security thanks to AI-driven fraud detection and decentralized identity verification for reducing scams in the crypto market. Further, he gave growth trajectories for cryptocurrency in Africa, noting that Africa’s cryptocurrency landscape represented a modest 2.7% of global transactions between July 2023 and June 2024.

TawkAfrica Spotlight reflects on Africa’s crypto boom in 2024, noting that cryptocurrency adoption in Africa reached new heights with over 50 million Africans now owning digital assets.1Africa’s Crypto Boom in 2024: Key Moments and Trends, Tawk Crypto (Dec. 26, 2024), https://tawkcrypto.com/africas-crypto-boom-in-2024-key-moments-and-trends/.1 This surge represents a major leap forward, driven by increasing awareness, economic necessity, and technological advancements. Wallet downloads rose by 22% compared to 2023, signaling growing interest in digital currencies. One of the standout trends was the explosion of peer-to-peer (P2P) trading, which allows users to bypass traditional financial systems. Platforms like Binance’s P2P marketplace processed a staggering $3 billion in transactions from African users alone, highlighting crypto’s growing role as a mainstream financial tool. Businesses from e-commerce stores in Lagos to cafés in Cape Town are also integrating cryptocurrency into their payment systems because transactions are faster and the fees are lower. TawkAfrica further reflects trends showing that Nigeria led in adoption with 40% of adults holding cryptocurrency, followed by Kenya, Ghana, and South Africa, where institutional and retail investors were seen to be embracing crypto.

Overall, Africa is rapidly emerging as a key player in the global cryptocurrency landscape. With increasing adoption, rising investment in blockchain startups, and evolving regulatory frameworks, digital currencies are creating a more inclusive, efficient, and resilient financial ecosystem across the continent. As crypto continues to gain traction, Africa’s digital financial future looks more promising than ever.

IfeOluwa Alabi shared perspectives on the complexities of jurisdictional requirements in digital disputes. He began by noting that in international arbitration, the tribunal’s power stems from the arbitration agreement. And he stated that a party objecting to the tribunal’s jurisdiction would typically raise issues about whether there is a valid arbitration agreement, whether the dispute falls within the scope of the arbitration agreement, and whether the tribunal has been properly constituted. He explained that these positions do not necessarily differ when dealing with digital disputes, but given the nature of these digital transactions, there is an added layer of complexity when assessing jurisdiction.

To understand the complexity, Alabi prompted the audience to think about digital assets, which are intangible, often cross-border, and sometimes exhibiting records of large series of ledgers in large networks of computers worldwide with touch points in multiple jurisdictions. Another layer of complexity is that parties to crypto transactions may be unidentifiable and untraceable. Further, cryptocurrency exchanges, non-fungible token (NFT) marketplaces, and platforms may not necessarily have a legal presence where the user comes from, given the global market. And these platforms may not have substantial assets for enforcement purposes in places where they have a legal presence. Cryptocurrencies, he noted, are held in a wallet and can be transferred to another part of the world immediately.

Alabi further expounded on what he terms the “three Musketeers” of jurisdiction. These are territorial jurisdiction, which is about which state has jurisdiction over a dispute when the assets and relevant persons are scattered across multiple jurisdictions. The second is personal jurisdiction, which points to the complexity of people being unidentifiable and untraceable, making it unclear whether certain laws apply to certain people. And the third is subject-matter jurisdiction, which relates to the arbitrability of digital disputes. In certain jurisdictions where cryptocurrency is still banned, there is an open question about whether crypto disputes will be arbitrable in those jurisdictions. A party therefore has room to challenge the jurisdiction of an arbitral tribunal in cases involving cryptocurrencies.

The choice of law also becomes a challenge, especially due to the above-mentioned cross-border nature of crypto transactions and the fact that traders are scattered in different jurisdictions, which complicates the resolution of disputes. Parties have also been seen to drag arbitration into litigation, for example, in the Binance arbitration where the parties litigated jurisdictional issues.2Lochan v. Binance Holdings Ltd., [2024] O.N.C.A. 784 (Can. Ont. C.A.).2 Parties can remedy these challenges by taking care to draft arbitration clauses that clearly designate the applicable law and forum to encourage effectiveness, reliability, and access to justice.

William Kirtley expounded on the ethical considerations and opportunities for crowdfunding in arbitration. He began by noting that arbitration clauses are often included in the terms of service of crowdfunding platforms. His address then focused on utilizing crowdfunding to fund both arbitration and litigation. He defined crowdfunding as the solicitation of small donations and investments, typically via online platforms, from a large group of unrelated supporters. He highlighted that this has increasingly been viewed as a way to secure financing for developing new ideas or supporting a particular objective. Having worked in Ivory Coast for two and a half years, he noted that this is relevant for Africa because at the time it was difficult to secure loans and even when secured, the interest rates were high.

In theory, crowdfunding is a potential way to avoid the interest-stricken bank loans when accessing capital. Practically, however, Kirtley explained that he worked with an organization whose goal was to fund arbitrations by crowdfunding, and he discussed some of the challenges, including that crowdfunding is time consuming, issues with the crowdfunding website, and user complaints about computer problems.

In terms of how the crowdfunding operated, users would upload a description of the nature of their case, the amount of funding sought, and the percentage of the damages they would offer the investors in return. Alternatively, users could seek simple donations where the investors would pledge to donate and if the fully pledged amount was raised, the parties would draw a standard litigation crowdfunding contract much like a third-party funding contract, which everyone would sign online. The same, however, was time consuming, especially because of user issues. The other challenge is that even though there was a huge number of individuals who wanted to crowdfund their disputes, there were far fewer people who wanted to invest money. This meant that there was far more demand than supply, which occurs even with traditional third-party funding. A number of users would also offer a relatively low reward, for instance, 3% of the litigation proceeds, in return for funding, ignoring the investor risk. As such, there was a disconnect between the actual value of claims in the online crowdfunded cases and the traditional third-party funders that demanded far higher returns of about 30% to 50% of the claim proceeds, which justified taking the investor risk.

Kirtley went on to state that crowdfunding in theory grants access to justice for wider groups of people than traditional third-party funding because, by multiplying the number of investors and commitments required, the risks are lower, which should allow parties to bring disputes that would otherwise be too costly. But in crowdfunding, depending on the campaign, some donors or investors would be expected to receive almost nothing in return for their funding.

Kirtley also raised a few ethical concerns. He gave examples of a number of litigations that have been crowdfunded, the most famous of which was Daniels v. Trump where Daniels raised funds on www.crowdjustice.com of over $500,000 in donations. Luigi Mangione, accused of killing UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson, is also crowdfunding his legal defense using a platform called www.givesendgo.com and has raised $901,356 of the expected $1,000,000 as of April 12, 2025. Litigation crowdfunding can work, as the examples demonstrate, but most cases that have seen success are those that touch on people’s emotions.

Kirtley finish by discussing challenges, noting that crowdfunding attracts many potential investors, which increases the risk of conflicts of interests. Issues also arise concerning the confidentiality of arbitration, considering the large number of investors that want to be kept informed on the progress of confidential disputes. Further, people seeking funding at times have to disclose a lot of information on the internet that can be used against them in the actual case. There is also the risk of frivolous claims. Settlement of the award-debt can also be a challenge where there are many investors. Another challenge is that the success of crowdfunding cases depends not only on the merits of the case but also its attractiveness to the public, making it hard to raise significant funds even where the claims are valid. Lastly, some lawyers may not be familiar with the legal and ethical obligations of lawyers in crowdfunded cases.

Alexis Foucard gave a presentation on third-party funding, setting out the general perspectives and the legal viewpoint. He defined third-party funding as a form of financing where the funder who has no interest in the dispute covers the necessary costs of the proceedings for the disputing party. This would be legal fees, arbitration costs, and expert witness fees. The funder may be entitled to a percentage of the proceeds of a successful outcome, which can be pre-determined depending on the agreement. The fund is not a loan, meaning that, if the dispute is not successful, one does not have to repay the funder. Litigation funding is often perceived as a means to facilitate access to justice because it enables parties who lack resources to file their claims. It can also be seen as a risk management tool, as sometimes parties may have enough money to cover their dispute costs and yet they opt for third-party funding to avoid assuming that risk.

In practice, it is a tough market considering that there are many cases that require funding, but funders are few. The process is all about ensuring that third-party funding is secured by allowing the funder to be sufficiently acquainted with the strengths of the case. This goes beyond jurisdiction, the merits of the case, expected quantum, and award enforcement. He further pointed that if you reach out to litigation funders or they reach out to you, one needs to do due diligence, which includes information on the claim, evidence, chances of success, etc., and after due diligence one can proceed to negotiate the funding agreement. The content of the agreement must stipulate how the costs will be paid, whether the lawyer will be paid, and whether the third-party funder will be paid.

Litigation funding is largely unregulated in Africa. In Nigeria, the Arbitration and Mediation Act of 2023 addressed arbitration and mediation funding, but litigation funding was not addressed. In some common law jurisdictions, such as Angola, Namibia, and Ghana, third-party funding is still very limited because of the doctrine of champerty, which generally prohibits a third party from funding a lawsuit in exchange for a share of any proceeds it may generate.

In addition to third-party funding, other forms of funding include insurance. An example is the Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA), a member of the World Bank Group, which promotes cross-border investment in developing countries by providing guarantees to investors and lenders. If an investor receives an award and does not get paid, MIGA may compensate the investor. MIGA insures investors against the risk of expropriation and the inability of the award-debtor to satisfy the award.

Ahead of the arbitration, one can enter into a contract with MIGA, as the insurer of the arbitral award. Once the insured party wins, they may start the enforcement proceedings; and, if the award debt has not been satisfied within the time stipulated in the contract with MIGA, then MIGA pays. Private insurance can also be considered to ensure one gets their money at the end of the process.

Aija Lejniece added to the discussion by highlighting the dispute resolution clauses for crypto platform user agreements. She noted some of the most popular arbitration institutions, including Judicial Arbitration and Mediation Services (JAMS), London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), American Arbitration Association (AAA), Singapore International Arbitration Centre (SIAC), Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC), International Institute for Conflict Prevention & Resolution (CPR), Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), and International Chamber of Commerce (ICC). She highlighted that different crypto platforms prefer different arbitration forums.

She also explained that some cryptocurrency exchange platforms use ad hoc arbitration or resort to national courts. OKX, for example, has ad hoc arbitration where parties have the liberty to agree on the forum. Where parties fail to agree, OKX submits to the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules and Malta Arbitration Centre as the appointing authority. FTX also used to have ad hoc arbitration before its collapse. On the other hand, HTX (formerly known as Huobi) is located in and governed by the laws of Seychelles and requires dispute resolution before the Seychelles national courts. Lejniece explained that this was a deterrence because it would be cumbersome for an international user to go to Seychelles for dispute resolution, and even where it is done remotely, one would still need to be acquainted with Seychelles laws.

Crypto platforms also have different governing laws and institutions depending on user location. For example, Metamax has Texas law and JAMS arbitration for users in the United States, the laws of England and Wales and LCIA arbitration for users in the United Kingdom, and Irish law and LCIA arbitration for users in Ireland. Gemini takes the same approach with National Arbitration & Mediation (NAM) arbitration for users in the United States, LCIA arbitration for users in the United Kingdom, and Centro de Arbitraje y Conciliación de la Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá arbitration for users in Colombia.

Falco Kreis gave the practical aspects of third-party funding, given his first-hand insight of a funder’s perspective. He noted that funders see cases as investments. The money they provide is used to pay lawyers, tribunals, court fees, and at times opposing counsel fees. All these costs are investments intended to generate a return. For third-party funders to invest, they have to assess the claim and understand all the relevant facts of the case. He noted that the job of the third-party funder is essentially to “trade on risks”. That means third-party funders do not shy away from risks, buy they demand full disclosure of all the risks associated with a case to enable them to understand their exposure. The third-party funder will consider the jurisdictional issues, liabilities, and quantum. Of further importance is the expected duration of the case. This means that, where arbitration fails, for example, and the dispute transitions to litigation, third-party funders will consider the entirety of the matter until the end of the litigation. They also consider the enforcement issues that arise after an arbitration award is rendered. Further, there needs to be a healthy relationship between the costs associated with the dispute and the claim at large. The rule of thumb is that the third-party funder will not provide more than 10% of the claimed amount. For example, if the claim is worth $20,000,000, the funder will only be willing to provide $2,000,000. The reason is that the third-party funder calculates their return on overtime. This means that the longer the case takes, the higher the multiple of the funder’s return. The risk is that eventually, what may remain for the claimant if the case is prolonged waters down over time. The risk of third-party funding is that if the claim is dismissed altogether, the claimant goes insolvent, or the award cannot be enforced, the investment is lost.

Conclusion

As crowdfunding and cryptocurrency gain traction across Africa, traditional legal frameworks are being tested, necessitating adaptive mechanisms, such as clear regulations and institutions, that will enable arbitration to address emerging disputes effectively and ensure the enforcement of arbitral awards. Key takeaways from the discussion highlighted the complexity of crypto disputes owing to the complex nature of the subject matter and jurisdictional issues, which can be remedied when parties include arbitration and choice-of-forum clauses in crowdfunding and cryptocurrency exchange agreements.

Considering the general lack of awareness in Africa, going forward, stakeholders, including legal practitioners, regulators, investors, and arbitration institutions, must collaborate to refine arbitration procedures, develop standardized dispute resolution mechanisms, and foster awareness of arbitration as a viable means of resolving conflicts in crypto sectors. By doing so, Africa can position itself as a hub for innovative dispute resolution, contrary to the current state where major crypto platforms have no preference for arbitration in any African forum, despite the continent’s growth in the crypto market. There is also the need to create awareness in Africa for using crowdfunding as a means to fund arbitration and litigation and ultimately enhance access to justice.